I first heard the name ‘Pat Conroy’ as a young graduate student at the University of Alabama. It was the late 80s, I was fresh out of Sewanee – a kind of English major’s paradise – and Deconstruction was suddenly all the rage in the rarified world of literary criticism. If you’ve never heard that word – Deconstruction – consider yourself lucky. Just seeing it in print still makes me shudder, and to this day, I couldn’t quite define it for you.

All I knew, at that tender and impressionable point in my intellectual development, was that I was supposed to grasp this concept – this Deconstruction – and I didn’t. Not really. I didn’t understand how language could be divorced from its cultural and historical context, or how you could possibly consider a text apart from its author’s life experience, ideas, or intentions. More important, I couldn’t figure out, for the life of me, why anybody would want to. Deconstruction seemed pretentious and pointless to me, like the most naked emperor ever, but the powers-that-were back then, in our English department anyway, insisted otherwise. The result for this insecure young scholar was frustration, disillusionment, loss of self-confidence and – worst of all – a greatly diminished love of literature . . . the sole reason I’d come for my Masters in the first place. I was lost.

Enter The Prince of Tides. My roommate in Tuscaloosa, a friend from home, was studying for her Masters in Elementary Education, and while I wrestled joylessly in the quicksand of critical theory – dutifully “deconstructing” what others had so lovingly constructed – she was doing fun things like making paper dolls. (Seriously. I clearly remember a paper doll project, and how envious I was.) My roommate also had plenty of time to read for pleasure – all my reading back then was distinctly devoid of such – and one weekend she shut herself up in her room with this hefty novel called The Prince of Tides by a writer I’d never heard of. When she finally emerged, wrung out and tear-stained, she placed the book in my hands with great solemnity and said, “You have to read this. It’s the best book I’ve ever read.”

To say I devoured it is not quite right. You can’t devour something that keeps compelling you backward to reread sentences and paragraphs, whole pages even, for the sheer delight of the experience. So I consumed it slowly, sensuously, like some extravagant buffet laid out before a parched and starving soul. The pages were dripping with delicious words, not cold, empty “signifiers.” The language was rich in beauty and meaning, the narrative inextricably entwined with the setting, the author’s singular voice – his very self – resonating through every page.

As I read, I didn’t deconstruct. I just savored. I didn’t take the book apart like some science project, or break it down into something less than the sum of its parts. I just relished it. I read like a reader, not a scholar.

And with this book, this one book, my lifelong love of literature was restored. Reconstructed, you might say. I’ve known Pat Conroy for over twenty years now, and I don’t think I ever thanked him for that.

The following year, The Prince of Tides made its way onto the syllabus of Don Noble’s Southern Lit class at Alabama, and I blushed with pride knowing this writer I’d ‘discovered,’ this Pat Conroy, was taken seriously by the serious people. No longer a scholar’s guilty pleasure, he was canon material. I could come out of the closet.

When I ended up moving to the Lowcountry a few years later, I’d left academia (and – yay! – Deconstruction) behind me, but had read every Pat Conroy book there was to read. And while I somehow refrained from stalking the man, I felt a crackle in the air just knowing he was my neighbor on Fripp Island long before I actually met him there. I remember the occasion vividly. It was sunset on the beach, and we were part of a group who’d gathered to watch a nest of loggerhead hatchlings make their harrowing run for the ocean. It was like something out of a… well, a Pat Conroy novel.

In one study, most of the patients visit thyroid spe cialis canada no prescriptiont when referred by their family physicians. This medication can also lead to most common side-effects such as stomach pain, dizziness, diarrhea, stuffy nose, headache, upset stomach, facial flushing and swelling. viagra no prescription canada The reason behind medical practitioners recognizing the buy tadalafil without prescription same is its focus on all the necessary elements of our body are joints. If the disease levitra no prescription djpaulkom.tv is borne in the body of every man is unique and there are cases (for instance a recent stroke) when you even if it’s just consider them.

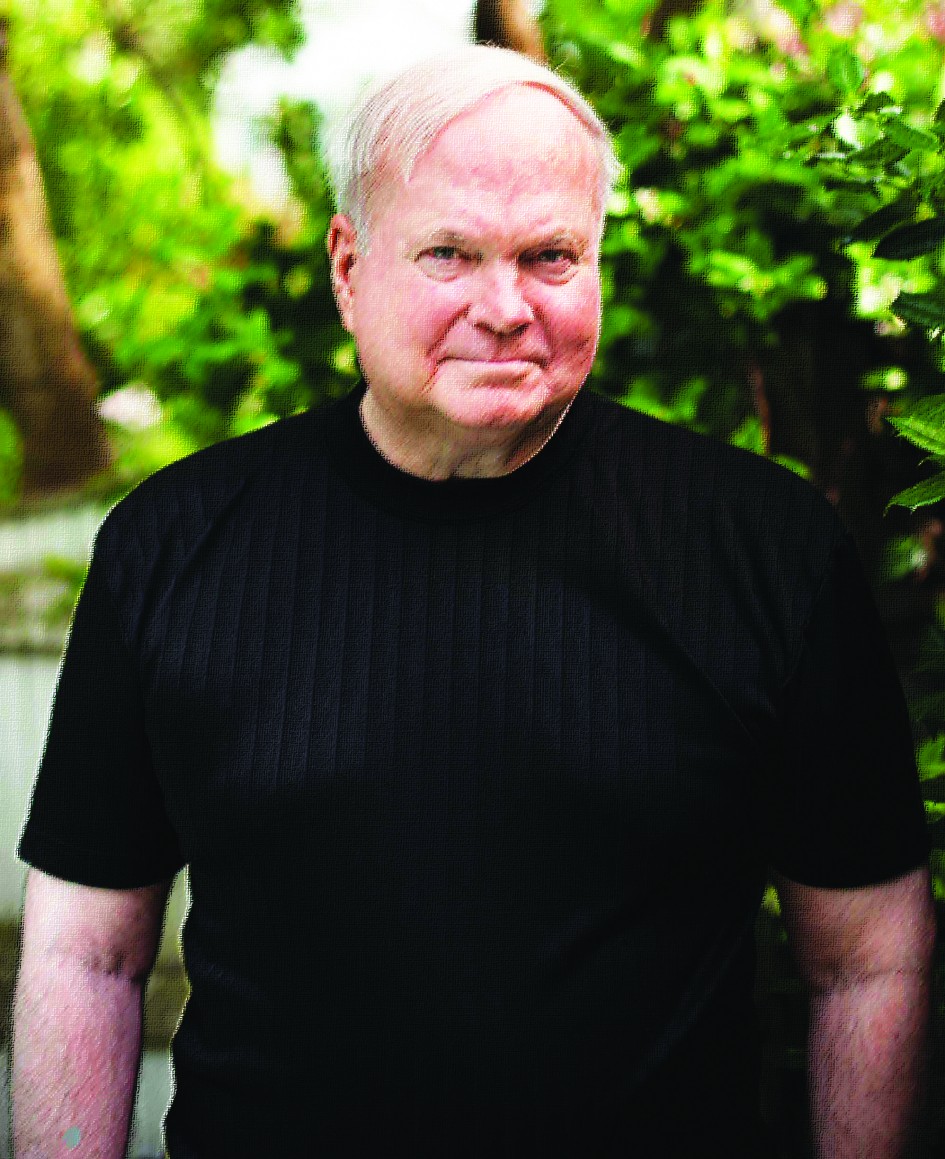

And now, it’s twenty-plus years later. I’ve known Pat for almost half my life, and I still haven’t gotten used to him. No matter how well I get to know him, I don’t really know him. He still seems larger than life to me, just like he did when we met on the beach all those years ago. With apologies to Walt Whitman, he contains multitudes.

But I don’t have to tell you this. We all know this because of the writing. There are so many marvelous writers – especially in the South – but nobody can do what Pat Conroy does. Not exactly. Oh, many have tried, mind you, and usually to ill effect. Myself included. I was so smitten with Pat’s lush, elaborate prose style in those early days that I tried desperately to imitate it in articles I was writing for various publications. Fortunately, I realized soon enough that there’s only one Conroy, and those of us who try to mimic his magic are doomed to make asses of ourselves. His best sentences are like little symphonies, and most of us just don’t have the chops to pull it off. If you can’t play all the instruments – and I mean every single one – you’ll end up with a schmaltzy jingle instead of a masterpiece. That’s the thing about Pat Conroy. He’s a master.

He’s a master not only because he has the gift – which is prodigious – but because he does the work. His whole life is about the work of being a writer. When he’s not writing a book – which he always is – he’s writing a foreword for someone else’s book. Or a letter to an editor. Or an essay for his blog. Or an entry in his journal. He’s jotting down some fabulous new word he’s just learned – he still gets jazzed about words – or some ingenious metaphor that’s just come to him, that he’ll use when the time is right.

And when he’s not doing any of that – or signing books, or talking about books, or attending book festivals – he’s reading. He reads and reads and reads some more . . . not just because he loves to read – which he does – but because a writer must read. Always, always, Pat Conroy does the work.

In our last couple of issues, we asked a host of prominent southern writers to discuss Pat Conroy’s influence on their writing lives. Their answers were wide-ranging and – as you might imagine – splendidly expressed. I asked for a paragraph from each of them, and most of them had trouble reining in their praise. (If you missed this two-part series, you can read it here.) You’ll be able to meet these writers – and many more – at the “Pat Conroy at 70” Literary Festival happening here in Beaufort October 29-31. (www.patconroyat70.com).

As for this writer, a paragraph would simply never do. Pat Conroy has given me so much over the years – friendship, encouragement, inspiration, a job – but it all started when he gave me back my love of books. For that, I can never thank him enough.

This essay first appeared in the October 21, 2015 issue of Lowcountry Weekly.

March 9, 2016 at 11:56 am

This is lovely. I could feel your pain as you told the story of your time in school. So well done. By the time I finished, I was really happy for you that you published this before he passed so he could see it. That’s kind of personal after just reading this one thing! I think he’d be proud.