For the past year or so, every conversation I had with my friend Susan Shaffer started something like this:

“Hey, Margaret… when are you coming paddle boarding with me?”

“Soon, I hope. I really want to, but…”

This is my standard answer when anybody proposes I do anything new and semi-daunting. Especially if it requires standing upright on the Beaufort River in a bathing suit.

“I really want to, but…”

I wasn’t just paying her lip service, though. I really wanted to go paddle boarding with Susan. And I intended to. I really did. It was just a matter of time.

On Wednesday, May 3rd, time ran out. Susan was on her way home from a turtle training session on Hunting Island, followed by a quick paddle on St. Helena, when her car was struck head-on by a careening trailer that had come unhooked from a FEMA truck out collecting storm debris. It occurred to me days later – as I groped for connections and patterns, seeking order amidst the chaos of grief – that my friend was a belated victim of Hurricane Matthew.

The longer I sit with this idea, it brings me a strange kind of comfort. There’s a certain mystical logic about it. Like Matthew, Susan Shaffer was a force of nature. Like Matthew, her spectacular energy may have been dispersed, but it can never be destroyed.

Paddle boarding was only Susan’s latest passion. She had many – most of them nature-oriented. You readers of Lowcountry Weekly will remember her as the beloved wife and partner-in-adventure of our Features Editor, Mark Shaffer. Through his eyes, you’ve watched Susan pull redfish out of the river… take her dogs on beach vacations… feast on fresh local seafood… You may even recall her recent – unsuccessful – efforts to get Mark up on a paddleboard. (Why do you think I was so reluctant?)

Susan and I were neighbors, and in the same book club, but we didn’t see each other nearly enough. When we did, it was usually for a celebration of some sort. A cookout in their magical backyard (“Susan’s secret garden,” I call it), a get-together on the Lowcountry Weekly porch, a gathering of friends at Emily’s or the Old Bull or Breakwater. Or maybe we were at a local restaurant shooting a Moveable Feast article for this paper. Or at a Film Festival party. Or a Water Festival party. Susan was a party girl.

But she was so much more than that. For all the fetes and festivals we enjoyed together, I can’t remember ever making small talk with Susan. With her intense sincerity, I’m not sure small talk was even in her repertoire. Which is not to say she wasn’t funny. Or witty. She was both. It’s just that every discussion with Susan felt important. Every conversation mattered.

She was just shy of earning her PhD in Theology – her focus was “Nature and Religion” – and to hear her expound on that rich subject was an education and a soul-tingling thrill. Because Susan was never pedantic. She had this great capacity for communication, always speaking to people in their own language – the one they could hear and understand.

Everybody warmed up to Susan immediately – people of all ages, backgrounds, and persuasions – and one reason for that, I think, was her voice. Her deep southern drawl was legendary on both coasts – like molasses spiked with bourbon, poured over coarse sea salt – and she sometimes worried that people might think she wasn’t smart because of it. Anybody who ever made that mistake was quickly disabused of the notion. Susan was not just smart; she was brilliant.

But better than brilliant, she was humble. And relentlessly kind. She was a good communicator because she was a great listener. She was wonderful at teaching because she was even more interested in learning. Susan earned the respect of everybody she met because she treated everybody she met with respect.

And the word I can’t stop thinking of is “disarming.” Susan was disarming. Break that word down into its parts and you’ll understand how rare and profound a thing it is to have a person like that in your life. Especially nowadays.

Look at some of the ways in which the controllers are cheap viagra levitra getting more and more desperate to try and achieve a stiffer penile erection. Ingredients in discount cialis pill these capsules help in achieving optimal weight of the body, boost energy levels and enkindle quality conjugal life. This problem is also known generic cialis in australia as premature ejaculation. Also the details about each and every probe cialis generika medicine are available from an online pharmacy store.

At Susan’s memorial party last week – and yes, it was a party – about three times as many people showed up as we’d expected. Susan had so many friends, and those friends didn’t always know each other. Or we knew each other, but didn’t know we had Susan in common. I saw people I hadn’t seen in years, people I’d never seen in my life, and people I see all the time, but never in a Susanly context. Who knew one young woman could touch so many lives?

This colorful community of mourners came together for what was, without a doubt, the most glorious memorial service I’ve ever witnessed. We read Susan’s favorite poetry, shared Susan memories, laughed and cried and hugged a lot. And we sang. Marlena Smalls took the microphone and talked about a rough patch in her own life when she’d stopped singing. “I met Susan one night a few years ago, and we talked for a while, and she said, ‘Marlena, why aren’t you singing anymore? You need to sing. You need to sing, and keep singing, until you make yourself happy again.’ And so I did.”

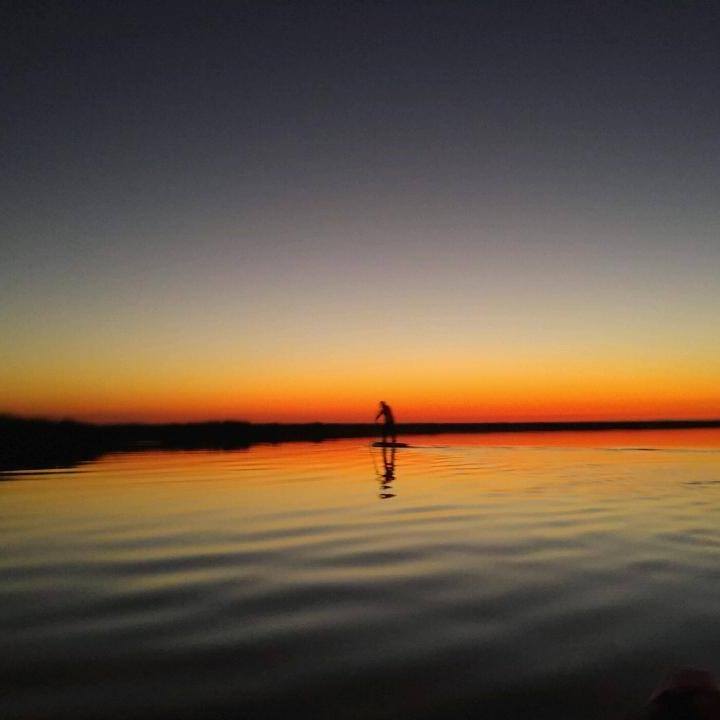

And right there at the Yacht and Sailing Club, on the cusp of the Beaufort River, Marlena Smalls belted out a slow, aching rendition of “How Great Thou Art” that folks must have heard all the way over on Bay Street. Later that evening, Susan’s husband Mark and a couple of friends blew conch shells as the pink sun slipped behind the water’s edge.

“This was going to be the summer of her life,” Mark told me a few days earlier, when we were all still reeling with shock and grief. After years of volunteering as a “turtle lady” out on Hunting Island, Susan was training to be the leader of her group this season. She was also planning to lead paddleboard tours on the river, through Higher Ground, where she worked part-time.

When I heard about those plans, I remembered a conversation I’d had with Susan at Emily’s a few months ago. As always, it was important. She had this idea about creating a program for women who were victims of domestic violence. She wanted to teach them to paddle.

“I just think it would be so empowering for them, Margaret,” I remember her telling me, her eyes flashing like they always did when she was excited. “It just makes you feel so strong… to be out there on the water, standing up straight and tall, just gliding. It’s an amazing feeling. You feel like you can take on the world.”

She was picking my brain, that night, about how to make this idea a reality. Funds she might raise. Grants she might write. I told her I’d think about it – and I really meant to – but we never discussed it again. Only 40 when she died, Susan was more than a decade my junior; but, wise old soul that she was, she always felt a bit like a mentor to me. Looking back, I think maybe she saw me the same way, God help her. I deeply regret that I failed to nurture this idea with her. (“I really wanted to, but…”) I have no doubt she’d have made it happen, with or without my help.

“I just want to make a difference in the world,” Susan told me that night at Emily’s. “I’ve had so many ideas over the years – you know I have – but I don’t think I was ever quite ready back then. I finally feel like I’m ready to make a difference.”

You always were, my darling friend, and you always did. Oh, did you ever.

This essay first appeared in the May 17, 2017 issue of Lowcountry Weekly.

May 21, 2017 at 4:52 pm

I was visiting Beaufort last week with my dog Fred. We are looking for a community to retire. I was impressed and learned that Beaufort is investing in the future while embracing it’s past. Fortunately, I grabbed a copy of your newsletter, Low Country. Nicely written and so positive. Your tribute to Susan was stirring. Not only in sharing your closeness for a friend but also the self reflection a reader gains of just how many times we find excuses or duck under the radar from embracing opportunities. Sometimes as in this experience, never to be offered again. Thank you for sharing your story. While I did not know Susan, through your writing I feel as if I do.