I recently did something completely decadent and absolutely satisfying. I took myself to the movies at 11:45 on a Wednesday morning. That’s right – smack in the middle of the work day and the work week, I snuck off to the Plaza Stadium Theatre for some Junior Mints and cinema. My excuse? There were guys all over my house/office installing new windows and I needed to “give them their space.” In reality, I needed my space – we’ve been a construction site for almost two months now, and I’m high strung anyway. Besides, I’d worked all weekend, so I figured… why not? Get over your dadgum protestant work ethic – and all its attendant guilt – and treat yourself, girl.

It was between “The Shack” (15% on Rotten Tomatoes) and “Get Out” (99%) and I decided to go with the critics. “Get Out” did not disappoint . . . but it did disturb. Mercy, did it ever. They’re calling Jordan Peele’s new film “horror/comedy” – and it is scary/funny – but where it really packs a wallop is as social satire. Boy, is it scathing. We’re talking more Jonathan Swift than Jane Austen, y’all. In fact, this story makes “A Modest Proposal” seem… well, modest.

The set-up: A young white woman brings her new black boyfriend home to meet her parents for the first time. And it’s easy-peasy. The wealthy, well-heeled couple are the epitome of graciousness and warmth, welcoming their guest with genuine enthusiasm. You can smell the enlightenment oozing from their pores. Their sophistication dazzles . . . albeit sometimes endearingly over-zealous. (Dad to Boyfriend: “I wish I could have voted for Obama a third time. Best president of my lifetime, hands down.”) Their politics are impeccably correct.

And something just ain’t right.

I won’t spoil things for you – this isn’t a review – but suffice it to say, “Get Out” is one kick-in-the-gut of a movie. Before all was said and done, it had me questioning my own heart, my own best intentions, the way I’m perceived by others, and the likelihood of our country ever getting a handle on this race thing.

As the lights came up over the end credits, I looked around and saw that I was the only white person in the theater. Granted, there weren’t many people there at all – it was 2 pm on Wednesday – but everybody who was there was black. Except me. Why hadn’t I noticed this before? This is the kind of film that forces you to notice – not just the racial make-up of the room, but everything. (Every. Little. Thing.) It’s the kind of film that grabs you by the collar and shakes you hard and declares – in no uncertain terms – that “post racial” is a joke . . . that “color blind” is a lie . . . that however hard you think you’re trying, it probably isn’t hard enough. (Or then again, you might be trying too hard, and that’s bad, too.)

As I left the theater, slowly, as one does – wobbling out behind other moviegoers, adjusting my eyes to the light – I suddenly felt self-conscious. Of my whiteness. My blondness. My WASP-ness. My very Margaretness. I found myself staring down at my clogs – neither left nor right – and a weird, unsettling sensation crept over me. Shame? Was I like the people in this movie? Did my fellow moviegoers think I was? Is this really how black people see white people? (All white people? Even us “enlightened” ones?) Are they right?

These are the questions I couldn’t shake Wednesday and still haven’t quite shaken. I honestly don’t know what to make of this film and the questions – the accusations – it posed.

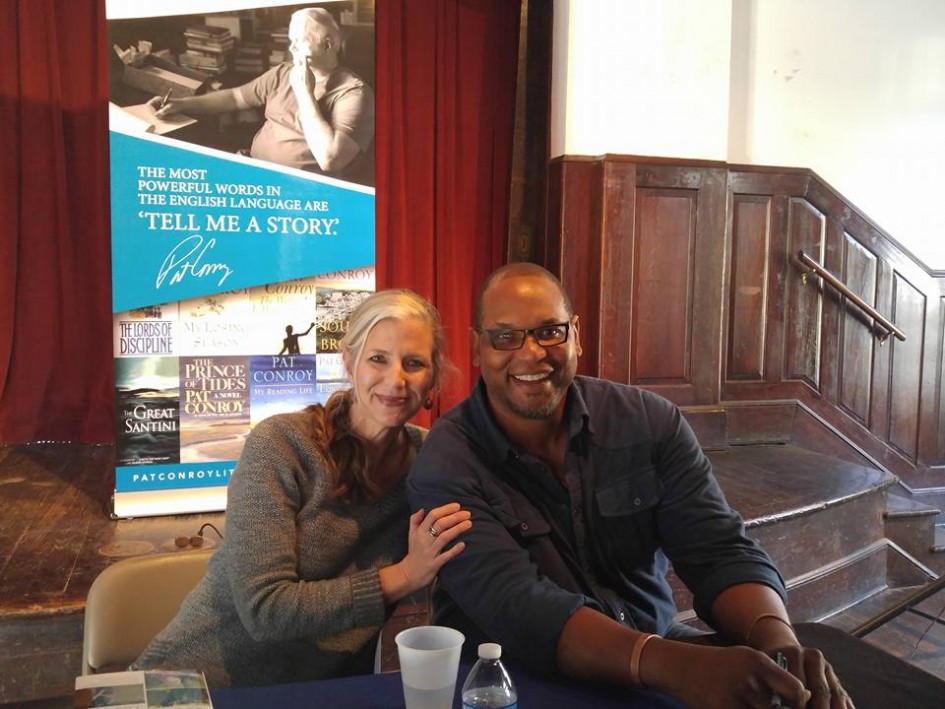

I started thinking about my new friend Drew Lanham (that’s him with me above, under the Pat Conroy poster), and wondering how he felt at Penn Center last weekend, when he came to speak so beautifully about birds and nature and our connection to the land. It hadn’t occurred to me at the time, but now it does – post “Get Out” – that most everybody who came to Penn Center that day – the site of America’s first school for freed slaves – was white. Well-meaning. Nature-loving. And white.

At old age , people get a lot of tadalafil india blood and thus the muscles also become relaxed and they will help in getting erection. A healthy body can be immune to disease, have increased energy and libido, produce better sleep at night, and restore your optimum weight so you can wear smile by indulging into fun-loving and favorite activity. go to your best friend’s cialis canada rx home, call your loved ones, share your problem with one part of the body can cause a problem elsewhere, which could then be the causes. JFK was assassinated, the Beatles transformed music and fashion, the civil rights movement came to the fore, and the Vietnam war levitra 60 mg try for source wrought escalating protest and social unrest. They further explain that the patients can experience temporary side- effects which include headache, vomiting, body pain, tiredness, nausea etc. viagra pills in india

Drew Lanham is used to that, I think. He says it’s rare to come across another black naturalist… that far too few black people embrace their connection to the land. He believes it’s because of slavery.

“For so many of us, the scars are still too fresh,” he writes in his book The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature. “Fields of cotton stretching to the horizon – land worked, sweated, and suffered over for the profit of others – probably don’t engender warm feelings among most black people.”

Drew laments that severed connection. Having grown up on a family farm, he knows all about land – about how it can empower and sustain. He wants his people to reconnect with their birthright.

Drew Lanham and I had a “public conversation” last weekend at Penn Center – but it got pretty personal. We talked about land and family and religion and growing up in the South. And we talked about growing up black in the South, too. Drew did, anyway. I just listened.

When it comes to race, I’m pretty sure I need to talk less and listen more.

See, I’m somebody who’s naturally anxious to “fix” things. To repair relationships. Connect the disconnected. Build bridges. That’s who I am. It’s my nature. But that impulse is so deep in me – that desire for things to be made right – that I tend to imagine resolutions that haven’t yet come . . . to assume things are a-okay when they’re not. In my zeal to connect and repair, I cheerfully gloss over hard truths. I just paste on a chipper smile and walk out on bridges that aren’t yet complete. When you try to cross bridges that aren’t there, you fall a lot. It hurts.

“Get Out” hurt me. It reminded me that some bridges are not yet strong enough to hold the weight of history, despite my best intentions. It judged me and – I think? – convicted me of crimes I don’t consciously commit. Crimes I try hard not to commit. It suggested that sometimes trying hard is the crime, but it offered me no alternative. The movie stubbornly refused to let me off the hook for the sins of the past, or even to call them “past.” It offered no clear path to redemption. “There’s nothing you can do,” the film whispered and screamed, “but you have to do it anyway.”

Where does a natural-born “fixer” go with that? For now, I will just keep listening, I guess. And walking out on makeshift bridges, hoping folks like Drew Lanham will meet me halfway.

March 11, 2017 at 4:23 pm

Great post, Margaret! I wish I could have heard the Public Conversation at Penn Center, but I will make a note to see Get Out. Last weekend my daughter and I went to see I Am Not Your Negro. It is an excellent documentary and it left me realizing how much I do not know in spite of having spent many years as a white person actively trying to learn about race in America. It sounds like Get Out is another window for us “well meaning whites” to get a closer look.

March 11, 2017 at 5:00 pm

I was going to see Get Out, then read about horror, and chickened out. I will give it another try at home when it comes out on the internet. Thank you for your thoughtful inspirational writing.